Art, // August 2, 2018

Terry Graff — ARTIST

Interview with ECO-DECO artist Terry Graff —

1. Who are you and what do you do?

I am a visual artist who currently lives in Island View, New Brunswick, in Canada, with my wife, Kim Leaver Graff, and four Siamese cats. With the support of Kim, I have been able to maintain an active studio practice throughout my adult life, while also enjoying a professional career in the visual arts as an art educator, curator, art writer, and director of four public art galleries in four different provinces of Canada. My studio has always been at my place of residence for both practical and economic reasons. When living in Sackville, New Brunswick, my studio was a 200-year-old Georgian-style house, where a muskrat lived in the basement, and where I ritualistically charred my decoy works in a wood furnace, and constructed a large immersive mechanized swamp (Tantra Mantra). My current studio comprises a large interior space, a barn, a double garage, and every other available space in our house.

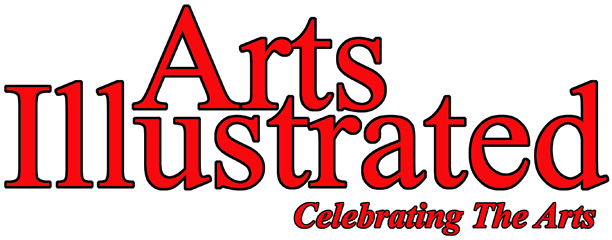

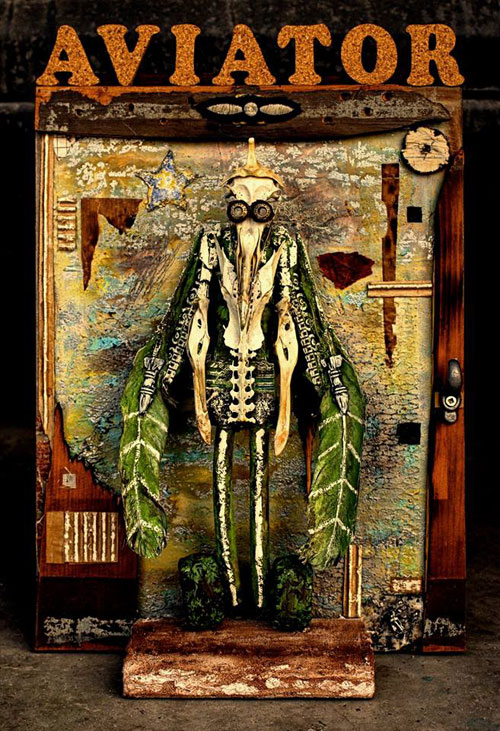

My work includes mixed media drawings, paintings, collages, assemblages, sculpture, kinetic works, and multi-media installations. As early as 1975, I began fusing images of ducks with machinery, a visual expression of the process of becoming modified or transformed for survival in a post-apocalyptic world. Over the years I have expanded on this theme with the creation of robotic duck decoys and mechanical simulations of wetland environments and other ecological systems, and futuristic aviaries that reference old-fashioned shooting galleries and pinball machines. My most recent work (The Warbird Series) continues my focus on hybridizations of nature and technology through the fusion of birds with war machinery and combat weaponry in a dark comedy of nature fighting back.

2. Why art?

I cannot imagine a world without art. Art is as vital as food, water, and air. It is a primal impulse that is imperative for perceiving and being in the world, for creating life experience, for self-actualization, for expanding one’s horizons, and for awakening the conscience of the world. Art is serious play. It triggers the imagination and creativity; it engages the mind, ignites the spirit, and feeds the soul. As a way of connecting with the mystery and magic of the universe, and as a pathway to both truth and beauty, art is what makes us human and gives meaning to life.

3. What is your earliest memory of wanting to be an artist?

I’ve always had a deep and all-consuming passion for expressing ideas and feelings by making art, so I don’t remember when I didn’t think of myself as an artist. As a kid growing up in the 1950s and 60s, I loved to draw and paint, and to build elaborate environments, such as carnivals and haunted houses in our backyard, and a “Wunderkammer” of insects, rocks, and bird skulls in my bedroom. My favourite toy as a kid was a bakelite View-Master, which presented magical 3-D dioramas that transported me to faraway places and fantasy worlds. My parents fuelled my enthusiasm for art by providing me with the largest box of pastels on the market at the time and all kinds of other art supplies. Since there were no formal art classes offered to children in my hometown of Galt(now called Cambridge), Ontario , they enrolled me in adult art classes at the local YWCA and at the historic house of Canadian painter Homer Watson in Doon. Although I was the youngest participant, I took the classes very seriously. My first ‘plein air’ painting was of a milkweed, which consisted of oil paint on canvas and numerous actual insects (flies, mosquitoes, moths, etc.) that flew into my work and got lodged in the paint. I was a precocious and curious child who had an early love of museums, and who started creating a library of art books while in public school, which today consists of thousands of books. I produced an impressive number of drawings and paintings, largely of birds and animals, which fortunately my mother saved for me. These works have given me much insight into who I was as a child, and I later referenced some of them in my work as adult. At age six, my Kindergarten teacher, let me paint a twenty-foot-long mural above the chalk board at the front of the classroom, and I won a tricycle on CKCO’s TV’s “Big Al’s Ranch Party” for my drawing of a Jack-in-the-pulpit, my favourite wildflower that I cultivated in my mother’s garden. Throughout my youth, I considered myself an artist and never wondered about what I should pursue in life. Art is what captured both my heart and mind.

4. What were the major influences on the development of your work?

My childhood is a very strong influence. I was lucky to have such an encouraging mother, and my father, the quintessential handyman and an inventor who had built his family’s home with his own hands, was a strong role model. Also, in my youth, living in industrial southern Ontario, I worked in various machine shops and factories on assembly and production lines, welded truck mufflers, grinded and riveted metal, and later handled car parts for General Motors, experiences that influenced both the content of my art and my interest in working with industrial materials. The disjunction between the uncreative, piecemeal work of the assembly line and my father’s resourcefulness with materials and intuitive understanding of machines, along with the conversion of the once natural landscape behind my childhood home into a parking lot, were significant factors in the direction and evolution of my practice and theoretical concerns. Many of my constructed decoys and mutant birds carry childhood memories and can be viewed as displaced victims of a fragmented socio-economic environment.

The Fine Art program at Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Technology in London, Ontario, was exactly what I needed after completing high school, as I found myself immersed in a highly creative studio environment with like-minded individuals, a place where all of the instructors were working artists. Fanshawe was an art incubator for experimenting with new ideas, forms, methods, media, and interpretations. It was established by Eric “Ricky” Atkinson, who had served as head of the Department of Fine Art at Leeds College of Art in England before immigrating to Canada. The American sculptor Don Bonham, who made fantastical fibre glass sculptures of cars, boats, and planes that combined human and machine forms, was one of my instructors and an important influence on me.

After three years of immersion in London’s dynamic art scene, I went on to further my studies in Europe at the Jan Van Eyck Academie, in Maastricht, Netherlands, and at several universities in both Canada (University of Guelph, University of Western Ontario, and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) and the USA, Wayne State University. In those years, I wasn’t interested in a career, only in learning, in absorbing as much as I could about the visual arts. For me, education has always been a life-long pursuit that has involved traveling to major museums around the world and talking to other artists. My thirst for new ideas and forms of art has never been quenched, which is why I sought employment in the public art gallery system. It enabled the opportunity to continue to learn by working directly with other artists.

5. How have you developed your career, and how do you navigate the art world?

I have always treated my personal art production as a sacred space and have never allowed the politics of the outside world with all of its power mongering, financial engineering, manipulation, exploitation, and corruption to affect it. I decided very early on that I would protect my inner child at all costs and not make any compromises with my art. To this end, I never pursued the goal of earning a living as an artist, but supported myself and my family by working in related fields, such as teaching art and gallery work. This strategy has ensured success and sustainability, as it allowed me to continue to dream and create without financial stress, and also to maintain and strengthen my self-identity and integrity as an artist. Today, I am financially secure because of early investments and can devote the majority of my time to my art practice.

In the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, I exhibited my “Eco-Deco” works both nationally and internationally in numerous public art galleries and artist-run spaces, and was the recipient of major sculpture commissions, acquisitions, grants, and awards. In the new millennium, I shifted my attention away from presenting my work within the traditional gallery system and staged self-initiated projects for particular audiences and select critical contexts. With the advent of social media, it has become very easy to connect with other artists around the world and to share my work beyond the confines of the museum. Most recently, I have joined a collective of artists, who make sophisticated Outsider artwork outside the mainstream of art in Canada, particularly that seen in Canadian commercial galleries. Each artist‘s work shows aspects of Outsider Art but it is not Folk art or artwork made in isolation. It often has, but isn’t limited to having, political or sociological content and it is not influenced by the contemporary art school and MFA aesthetic. Some of our members have no formal art education and are self-taught. Others have art school and MFA backgrounds but do not follow in that tradition. We make art that is true, genuine, and unique. Aspects of our work we hold in common are the use of recycled materials, the emphasis on Collage and Assemblage, and the freedom to do any type of work we wish to do. Above all we avoid being constrained.” See more work at the Remix Gallery Collective and on Facebook.

6. Describe your creative process?

I work on several pieces at once that vary in both size and medium. Some works happen very quickly, others take months, even years to fully realize. Making work for me is like working on a puzzle, moving things around in both my mind and in actuality until everything feels just right. It’s an intuitive thing. When all is going well it’s like riding a wave, or being in the zone, an experience where time, space, thoughts of the personal ego, etc., disappear.

“Ecological Vision”, the idea that the world is an ecosystem possessing a collective memory, that we are integrally connected and biologically wired to connect with nature, informs my creative process. Everything that happens, no matter how insignificant, in some way and at some time, affects the existence of everything within that system. I like to believe art has that same potential. By its very nature, the creative process has the potential to open us up to complex interrelationships between ourselves and others, and between living organisms and the living and non-living components and processes in the environments we inhabit.

Recycling and re-use of discarded materials and objects in my work has long been an important part of my process. The art supplies I use to create my “Eco-Deco” works were acquired by dumpster-diving and visiting the town dump. I once spent several months picking up pieces of discarded truck tires from the Trans-Canada Highway and converting them into sculpture. For “Cosmic Sea”, a large-scale public sculpture commissioned for Purdy’s Wharf Tower II in Halifax, I used garbage salvaged from Halifax Harbour and transformed it into mutated fish forms. The alchemical transformation that occurs through recombination of cast-off detritus from our consumerist, technological society provides me with a potent means for realizing my personal vision.

7. What do you aim to say through your work?

A consistent theme running through my work is how we are plagued by the contradictions of existence, by our dual character as part of nature yet transformed by technology. We live in a machine oriented rather than biologically oriented world, teetering at a dangerous crossroads between chaos and control, extinction and rebirth.

In the tradition of George Orwell, who used animals to satirize the human predicament and expose issues of injustice, exploitation and inequality in society, I use images of ducks and other birds as a vehicle for expressing the dark and often violent technological world we have come to inhabit. My early kinetic duck works, which playfully reference the innovative automata made by the French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson (1709 –1782), speak to how nature has been replaced and displaced by machines. Vaucanson’s mechanical duck “The Digesting Duck” had over 400 moving parts in each wing alone, and could flap its wings, drink water, digest grain, and even defecate. Currently my work focuses on two of the most urgent abominations and moral crimes perpetuated with humanity’s technological innovation: the destruction of the nonhuman world and the culture of war.

8. What has been the public response to your work?

Over the years I’ve received much critical feedback from people from all walks of life. I like it when my art provokes curiosity and discussion, and have enjoyed being confronted by basic questions like “why?” or “what?”, such as the time I set one of my decoys on fire and sent it over Niagara Falls. My response is to turn the questions back on the viewers, to ask them what they see and think and feel, and to leave room for them to come to their own conclusions. Although current social and political issues often influence my art, I don’t make didactic or overtly partisan or consciously political art. I have no interest in detailing what I think about real world problems and events, and don’t always have an answer or interpretation for my work. Art, by its very nature, is a portal to the unconscious mind, the deepest part of our being, and often confounds our analytical selves.

I have many stories about viewers’ responses to my work. Once, on my way to install an exhibition in Cambridge, Ontario, one of my large-scale assemblages (Dux Ex Machina Nesting Station) blew off the roof rack of my vehicle and shattered into multiple pieces on Highway 401. Undeterred, I pulled over, picked up the pieces, reassembled them into a different configuration at the side of the road, and delivered my work on time for the installation. The make-shift altered work ended up receiving critical attention for its “innovative use of materials and ‘road warrior’ patina.”

The following is a sampling of comments about my work by professional curators and art critics –

“Although highly critical of mankind’s destructive insistence on reducing nature to a utilitarian object, Graff uses industrial materials and mechanical devices to examine ecological issues. Is this irony or paradox? Does this constitute acceptance or rejection, surrender or victory? . . . Is this garish funhouse the end of nature, or is there the suggestion of regeneration and renewal after the deluge? Is it a dark parody of a technological world rapidly spinning out of control, or is it prophetic of a new natural order emerging from the ruins of a technological cataclysm?” –Robert Reid

“The bright, faucet-head-eye of the decoy, the probing phallic bill, the scatological feathered tail, of Graff’s burlesque ducks serve to deflate, invert, and shatter arrogant rational imposition of hierarchical values. The humour of metaphor and allegory links micro- and macrocosm in nature, satirizing the preposterous blindness of reason.” — Ted Fraser

“What sets Terry Graff’s work apart from other environmental or “eco-art” is humour. Many artists who deal with ecological themes take themselves far too seriously and bore the public to death with their pious preaching. Graff can make us think about serious issues and laugh simultaneously – it is one sign of a mature artist.” — Virgil Hammock

Finally, perhaps the most unusual response to my work was not from human beings, but from ducks. I constructed an extensive series of decoys from found objects, loaded them into my station wagon, and chauffeured them to a nearby duck pond. The purpose for this action was to introduce my art to a group of unsuspecting, although curious, mallards, in an experiment on how abstract a decoy had to be before its powers to deceive broke down, before it would no longer be read as the real thing in nature. I was absorbed by how images could be mistaken for objects and how objects could be mistaken for images. In Duchampian spirit, I completed this ironic discourse by including four live ducks in an exhibition of my work. Of course they defecated all over the gallery floor. In both cases, the ducks were active participants in the creation of my art.

9. What are you currently working on?

In the last few years my work has focused primarily on the subject of war and its culture, which has been an integral and consistent, if not dominant and inevitable, characteristic of the human condition throughout the history of civilization.

The theme of war in the visual arts was most commonly represented as a heroic enterprise before Francisco Goya (1746–1828) depicted the unspeakable horrors of military conflict. Following his lead, and a century later, Otto Dix (1891–1969) graphically relayed the harsh brutality of front-line battle with images of rotted skulls and broken bodies. For my contribution, I have elected to create a tableau of black humor involving “Warbirds” of all shapes and sizes transformed into lethal mechanized killing machines. Imagine a cross between Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds” and Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” or Stanley Kubrick’s “Full Metal Jacket.”

In Hitchcock’s “The Birds”, Mrs. Bundy states: “Birds have been on this planet since archaeopteryx, Miss Daniels; a hundred and twenty million years ago! Doesn’t it seem odd that they’d wait all that time to start a… a war against humanity?” Miss Daniels responds: “Maybe they’re all protecting the species. Maybe they’re tired of being shot at and roasted in ovens and… I don’t know anything about birds except that they’re attacking this town.”

The Warbirds series is a way of expressing what it means to be alive in the 21st century in a dark and violent world of political, cultural and social decay, where war and the threat of war persist while at the same time the planet’s bio-systems are being destroyed and wildlife is driven to extinction.

10. What advice would you give to younger artists who are just starting out?

Be true to yourself and follow your passion. Let your inner child be your guide, and make art for no other reason than the love of making art. Being an artist takes total commitment. It’s not a career; it’s a calling. Keep an open mind and seek knowledge and wisdom. Be courageous and not afraid to make mistakes. You will find your personal vision and discover who you are if you push yourself to take risks. Above all, show up in your studio and do the work.

LINKS —

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/terry.graff.14

Remix Gallery Collective: https://sites.google.com/view/remixgallery/home